Researchers leverage AI to fight online hate speech

Any frequent denizen of cyberspace can confirm that online hate speech is a widespread issue. With our daily lives becoming increasingly virtual, and would-be perpetrators emboldened by the anonymity of the digital space, online hate and harassment have risen to unprecedented heights.

A recent survey on online hate and harassment by the Anti-Defamation League shows that over half of American adults report being harassed online at some point in their lives; over a quarter have experienced online harassment just within the last year. “Overall, reports of each type of hate and harassment increased by nearly every measure and within almost every demographic group,” the survey finds.

Efforts to address online hate speech have faced significant hurdles, however. Online content moderation is often the subject of controversy, straddling a fine line between protecting free speech and safeguarding internet users from harm. Emerging innovations are tasked with fostering digital environments free from toxicity and discrimination while also avoiding censorship of inaccurately flagged language.

Rising to this challenge is an innovative solution recently developed by researchers at the University of Michigan and Microsoft, which combines cutting-edge deep learning models with traditional rule-based approaches to better identify hateful speech online. This approach is reported in their paper titled Rule By Example: Harnessing Logical Rules for Explainable Hate Speech Detection, presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL).

“More and more tech companies and online platforms are developing automated tools to detect and moderate harmful content,” said Christopher Clarke, doctoral student in computer science and engineering at U-M and lead author of the study. “But the methods we’ve seen so far have a lot of room for improvement.”

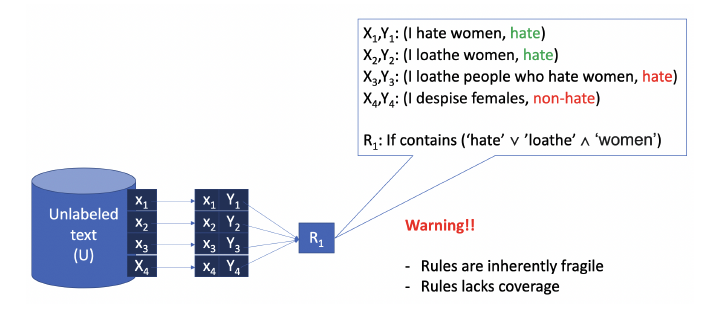

Traditional methods for hate speech detection are rule-based, meaning they operate based on set guidelines concerning what constitutes harmful speech, often taking the form of block lists or keyword flagging. Although attractive due to their transparency and customizability, these methods have proven largely insufficient; they are difficult to scale and the rules they rely on to dictate what is flagged do not adequately capture the context and nuances of online content.

“Detecting hate speech and toxicity is a subjective task, and language is very ambiguous,” said Clarke. “It is relatively easy for users to switch around tokens and bypass a rule-based system, so these methods are quite fragile.”

Data-driven deep learning methods have emerged as a promising alternative for online content moderation. Such models are trained on large amounts of data and leverage deep neural networks to learn richer, more accurate representations and generalize these representations to new data. Despite their improvements in accuracy compared to one-size-fits-all rule-based approaches, the application of deep learning techniques is not without challenges.

“With out-of-the-box, pre-trained models, the user inputs some text and the model generates a prediction and a probability score as to whether the content is hateful or not,” said Clarke. “The main issue with these models is a lack of transparency—users aren’t able to see or understand what the model is learning and how it could be improved.”

The failure of deep learning models to give users any explanation or guidance as to the reasoning behind their choices has hindered their widespread adoption and has added to growing distrust among consumers.

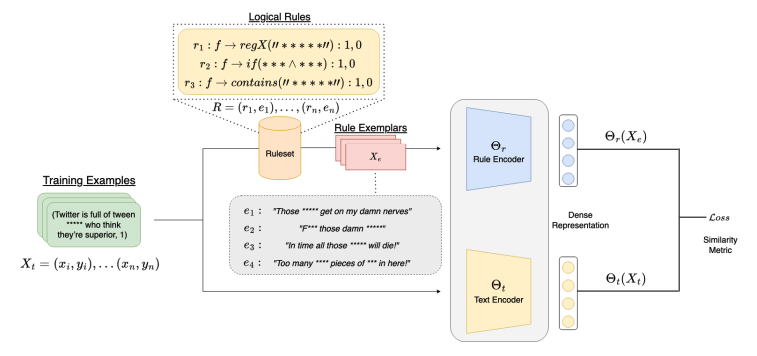

Seeking to harness the enhanced performance of deep learning models while preserving the transparency and customizability of rule-based methods, Clarke and his coauthors developed Rule By Example (RBE), an exemplar-based approach that uses deep learning to compare text inputs with examples of hateful content.

“RBE is a contrastive learning framework that pairs rules with what we call exemplars, examples of text that defines a given rule,” said Clarke. “The framework pairs logical rules that are very explainable with these exemplars and then encodes and learns them.”

To accomplish this, RBE relies on two neural networks: a rule encoder as well as a text encoder. Using these tools, the model learns robust, accurate embeddings of hateful content and the rules behind them, enabling it to accurately predict and classify online hate speech.

This groundbreaking two-part framework also solves the persistent issue of transparency that other deep learning models demonstrate. It gives users a clear picture of how its predictions are formed as well as the option to revise the rules being used.

“RBE displays what we call rule grounding, allowing users to trace back model predictions directly to the rules that govern them as well as the examples tied to those rules,” said Clarke.

Instead of only receiving a prediction and probability score, as with other deep learning methods, RBE allows users to see the factors that influence the model’s precision, building in transparency without sacrificing performance.

RBE also boasts exceptional customizability. Its unique grounding feature means that customers can edit the rules and examples influencing predictions in real-time without having to retrain the model.

RBE’s unique two-step approach combines the best of both worlds, preserving the advantages of deep learning models and rule-based techniques, ultimately yielding a hate speech detection system that is robust, accurate, and transparent.

“Our approach not only ensures greater transparency, but also enhances performance,” said Clarke. “RBE outperforms several benchmarks and actually shows better performance than existing hate speech classifiers.”

In fact, compared to the closest competing classifier, RBE showed a 2% increase in accuracy, a substantial difference considering the massive amounts of online data these models process. Together with its built-in transparency mechanism, this performance boost demonstrates RBE’s potential to significantly improve online content moderation and make digital spaces safer for everyone.

The goal is to integrate RBE into Microsoft Cloud, and plans are underway to patent this new technology. In the future, Clarke and his collaborators are also hoping to push RBE’s capabilities even further, testing its ability to accommodate more complex rules and extending it to other classification tasks, such as predicting the intent behind a given piece of text.

In all, the hope is that RBE and its future iterations will benefit end users by broadening protections against online hate speech and harassment while preserving openness and transparency.

Clarke’s coauthors on the above paper are Prof. Jason Mars of U-M as well as Matthew Hall, Gaurav Mittal, Ye Yu, Sandra Sajeev, and Mei Chen of Microsoft.

MENU

MENU